Permission obtained from The Gunpowder Plot Society to publish research from their website:

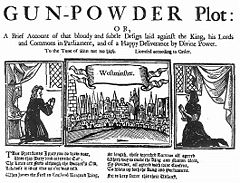

Four hundred and fifteen years have elapsed since the memorable Gunpowder Plot; yet so great was the perversion of circumstances connected with this atrocious act by religious and political parties, that it is was two centuries before a true knowledge of the event was uncovered. Indeed, even now some of is still masked in mystery. It was the policy of James I, and his Ministers, to represent the Gunpowder Plot as having been encouraged by the Pope and approved of by the great body of Roman Catholics in England. For this purpose, before the trial of the conspirators, an artfully concocted, but dishonest narrative, entitled “A Discourse of the Gunpowder Plot” was industriously circulated in England and, after translation into various languages, was diligently spread over every part of Europe. In the published account of the examinations and trial of the suspected parties, the evidence is misrepresented in some parts and altogether suppressed in others. The result of these and similar measures to deceive the world, has been to leave everything concerning ‘the plot’ by Roman Catholics to destroy The King, Lords and Commons in doubt and questionable almost to the present day.

There has been much research made among documents relating to this plot in the State Paper and in the Crown Offices. It was well known that upon the accession of James I to the English throne the Roman Catholics of the realm had good reasons for presuming that they would no longer be subjected to the oppression which they had endured during the reign of Elizabeth. The new Monarch was born of Catholic parents, and it was said approved of several ordinances of the Roman Church. Indeed, some declared that the King had given express assurance before he came to England of his intentions to tolerate the Roman Catholic religion. One of the early acts of his reign seemed to confirm this intention. He arrived in London in the beginning of April, in the July he sent for many recusants of distinction who were assured by the Lords of the Privy Council that “it was his Majesty’s intention to exonerate the English Roman Catholics from the pecuniary fine of £20 a month for recusancy imposed by the statute of Elizabeth”. For two years after this assurance the fines for recusancy appear to have been nearly all remitted. But the Roman Catholics soon discovered from the treats and declarations of James I that he had no intention of granting them toleration.