The earliest official form of body guard of which anything is known is that of the Sergeants-at-Arms who were mounted guards raised by Richard 1 in 1191. They were originally sons of knights, and later patents were granted to esquires. By the 15th century however, their role had been extended in such a way that the protection of the sovereign was no longer their first duty.

The Body Guard's History

This is a detailed history of the Body Guard since 1485. The research of esteemed historians such as Dr Anita Hewerdine has, with permission, been used. Other's works have been acknowledged accordingly. Click here for Further Reading .

The first positive mention of a royal guard in English history is found in the records of Edward I’s reign (1272–1307), where the description occurs “Crossbow men of the Household”. Nothing is actually known of this guard beyond the fact that it had a very short existence, as it is not mentioned again, and the long-bow was then becoming the national weapon, being much quicker in performance. The State records of Edward II’s reign mention:

“archers on foote for garde of the Kinge’s body who shall go before the Kinge as he traveleth through the countrye”

Edward II maintained this guard of archers, increasing its size and giving it thus a certain permanency, which had not previously existed. Each successive monarch since this time may be assumed to have enrolled a personal Body Guard, though details are not now available in all cases, certainly Henry V, the hero of Agincourt in 1415, and his “Archers of the Household” who accompanied him abroad and fought with him on the battlefield. These were maintained until the reduction of Henry VI’s household in 1454, when the Wars of the Roses put an end to all but hereditary State and Household appointments.

There had been a long dynastic power struggle even before the forty years of battles (Wars of the Roses) between the descendants of King Edward III. The feuding bloodlines, or Houses, the House of Lancaster (its badge being a red rose) and the House of York (its badge being a white rose) fought for the possession of the Crown of England and the power, wealth and influence that went with it. The Wars of the Roses began at St Albans in 1455 and saw the weak Lancastrian King Henry VI (he often suffered from bouts of madness) deposed by the House of York and the new King, Edward IV, enthroned in 1461. In 1483, and seventeen battles later, a fourth King, Richard III (House of York) became Sovereign of England but by now, and thousands dead in battle, the rival Houses wished for peace. The decision was that the throne should be offered to Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, on condition that he marry Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Edward IV, thus uniting the Houses of York and Lancaster and ending this costly war both in money and lives. Henry Tudor accepted the invitation and eventually embarked from Harfleur, France, for England in July 1485 with his “private guard of faithful followers,” and a small military force of about 2000 men. Being himself of Welsh extraction, most of his adherents being Welshmen, and his private guard being Welsh born, it was but natural that Henry Tudor selected Wales as his base. He stepped ashore at the village of Dale in Milford Haven on the 1 August 1485; he was soon joined by the Welsh, who flocked to his Standard. With an increasing force Henry pressed forward to attack King Richard III.

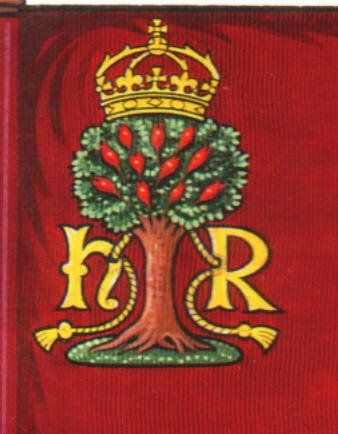

On the Eve of St Bartholomew's Day, 22 August 1485, they met at the Battle of Bosworth Field. Richard III was killed and it is said that the Royal crown, that he had worn over his helmet on the battle field, was found in a hawthorn bush by Henry’s “private guard”. The crown was placed on the head of Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, who was then and there hailed as King Henry VII of England. This historical episode was commemorated in the Henry VII Chapel, Westminster Abbey, by his son Henry VIII after his death in 1509. There, in its stained-glass windows can be seen at the present day, the design of the Crown on the hawthorn bush under the Tudor rose, with the initials HR on the sides. From Bosworth, King Henry proceeded to Leicester and thence to London, where, on the 1 September, he attended a Thanksgiving Service at St Paul’s Cathedral, and deposited there the three Standards under which he had fought and those he had captured on the field of battle. Hall, the historian, described them minutely, “The first had an Image of St George; the second, ‘a Fiery Dragon beaton on white and green sarsenet,’ the Ensign of Cadwaladr, the last King of the Britons; the third was of ‘Yellow Tartine’ on which was painted a ‘Donne Kowe’ which being interpreted means dun cow.” Henry VII was surrounded by his “private guard” of fifty men, now known as the Yeomen Guard or the Yeoman Archers.

It may well be asked why Henry did not retain the name “Archers” of the Guard, seeing that it was these archers who had become the terror of the men-at-arms and won the glorious victories of Crecy and Poitiers, and defeated the hitherto invincible mailed cavalry. Historians of the time say that there is no doubt King Henry VII conferred the title of Yeomen of the Guard as a proclamation to the people that he had selected his body-guard not from the nobility, but from that class just below them who had proved themselves as the national strength of the country at home and abroad. In the pardons granted by the King on his Accession, this class is described as “Yeomen or Gentlemen just below the rank of Esquire.” Such was the status of the Yeomen of the fifteenth century.

The designation “Yeoman” is of interest, as it was introduced for the first time into the Body Guard upon the institution of this permanent body. As far as the etymology of the word is concerned, the most probable origin is believed to be a derivation from “gau”, meaning “district” and the word “man” signifying “man of the district”.

The term “yeoman” had for some time been applied to subordinate members of the sovereign’s household, but previous Body Guards had been designated “The Cross-Bowmen of the Household”, “Archers of The Guard”, “Archers of the Crown”, “Archers of the Household”, “The Body Archers”, or “The King’s Bowmen”. The 14th and 15th centuries, the golden period of English agriculture, saw the rise and prominence of the yeoman class and its recognition by the State. The yeomen helped to fill in a large gap between the upper class and the labourers. They lived well and in the winter did not have to contend with the hunger and cold endured by those who served them. Thus they were well suited to make fine soldiers, for as a wise statesman propounded "To make good infantry it requireth men bred not in a servile and indigent fashion, but in some free and plentiful manner". The rewards granted took the form of appointments, such as bailiffs of certain towns, keepers of parks or castles, carrying emoluments, fees, commodities and profits.

The title of “The Queen’s (or King’s) Body Guard of the Yeomen of The Guard” has persisted to the present day, though during the Victorian era it had been altered to “The Royal Guard”. Before leaving the subject of correct designations, it is intriguing to discover the origin of misapprehensions, which have arisen in relation to the Yeomen of The Guard. A common acceptation of the work “yeoman” as coming from the “yeu”, the wood from which bows were then made, is as incorrect as the assumption that the yew trees of this country provided the source of our bows. In fact the best bows were imported from abroad, being mad from yew trees grown slowly on high ground in a dry climate.

The Queen’s Body Guard of the Yeomen of the Guard is now the oldest Royal Body Guard, and also the oldest military corps now existing in this or any other country, pre-dating the Gentlemen-at-Arms by 24 years and the Queen's Body Guard for Scotland, The Royal Company of Archers, who were founded in 1676. Though The Body Guard can be traced to the armed personal guards of the Saxon and Norman Sovereigns, its real historical origin is to be found in the body guards of the Plantagenet Kings of eight hundred years ago. These latter guards however, were known by various designations, such as “Cross Bowmen of the Household,” and “Archers of the Guard of the King’s Body,” and were often created anew by the Monarch on his accession. It was King Henry VII, the first of the Tudor dynasty, to make his Royal Body Guard a permanent institution and confer on it a definite title, a title it continues to hold.

Since its creation as a permanent Corps, the Body Guard of the Yeomen of the Guard has an absolutely unbroken history of over 535 years; for even during the brief period of The Commonwealth between 1649-1659 it continued to serve with King Charles II during his enforced absence in France, and at the Restoration accompanied him on his return to England, took its historic place in his triumphal entry into London, and stood around him at his immediate Coronation.

The last personal appearance on the battlefield of an English monarch surrounded by his Body Guard was George II who won a glorious victory against the French at the Battle of Dettingen in 1743. And between 1720 and 1830 a certain civilian element was admitted to The Body Guard but upon the accession of William IV in 1830 his majesty commanded that in future no one could belong to his Body Guard who had not served in the regular Army or Marines. Furthermore, it was stipulated that no one under the rank of Captain could become an Officer and no one under the rank of Sergeant could be a Yeoman in the King’s Body Guard.

The Officers and Yeomen of The Guard are re-sworn under each new Sovereign, and their ancient privileges are confirmed.

Apart from the guarding of the outer doors of the Palaces and doors to ante-rooms, they lined the approaches to the audience chambers at all state ceremonies, and accompanied their sovereign whenever he went out. The most elaborate precautions were taken in serving the Royal dinner, when one of the Yeomen would be required to take a sample of the food before it was permitted to go forward to the King’s table. Even the making the King’s bed had its own set of rules and to this day the connection with this ancient and quaint ceremony is maintained in the descriptions affixed to the names of certain yeomen on the Muster Rolls – YBH (Yeoman of Bed Hanger) and YBG (Yeoman Bed Goer) – though, needless to say, the duties concerned have long been obsolete. It is relevant to note, however, that these estimable duties extended to the ‘viewing of such houses as should be fit to entertain his Majesty’ on progresses through the country, which was a feature of Tudor times.

As previously stated, the position of Captain of The Guard was of particular significance. Not only was he answerable for the sovereign’s personal safety, but he also carried the responsibility for ensuring that all details of court ceremony were accurately performed. In addition, it was his duty to look after and protect, together with the Yeomen, important guests such as foreign potentates and ambassadors, escorting them to and from the royal presence. Indeed, on many occasions the Captain was actually dispatched abroad, accompanied by a group of Yeomen, to escort diplomatic missions to great emperors or kings, or to act himself as an ambassador. Negotiations for royal marriages were often included in such missions. In cases where a noble had to be arrested, perhaps for plotting against the sovereign, the Captain was responsible for apprehending him. Several times in their history the Yeomen of The Guard found themselves in the ironic position of having to seize a great or royal personage who, a few years earlier, had actually come under their protection. Such was the fate of Cardinal Wolsey, the Lord Protector Somerset, and Anne Boleyn.

The appointments of Captain of The Guard and Vice-Chamberlain were held by one official until towards the end of the 17th century. As the daily duties of The Guard in attendance on the Sovereign gradually diminished, the connection of the two appointments became unnecessary and was finally severed. The Vice-Chamberlain became a separate appointment and was bestowed on an official whose duties were of a less important nature. Whilst the Captaincy of The Guard, shorn of its daily and hourly responsibilities, became a ministerial and honourable sinecure, as it is at the present day. Though no longer Vice-Chamberlain, the Captain is under the direct orders of the Lord Chamberlain, and with The Guard attends his Sovereign, as a member of the Royal household, on all state occasions.

The Clerk of the Cheque had special responsibility for maintaining the roll of everyone connected with the royal household, in addition to handling large sums of money in his capacity of paymaster. Until modern times a portion of The Guard was mounted, as a travelling escort to the monarchs of England. The Yeomen of The Guard figure prominently in a number of old engravings and examples of sculpture, in some instances being shown on horse back, always very closed to the Sovereign’s person whether in representations of battles or ceremonial occasions.

In addition to attending the sovereign, the Yeomen were also called upon to serve the Queen and heir to the throne. During George III’s long illness, the Prince of Wales became Regent, in 1811. The King’s portion of the Yeomen of The Guard was transferred to Carlton House, where Prince George resided. This led to a significant change in the board and pay of The Guard. At the time, the yeomen were the only court officials still receiving their meals at St James Palace, which it was then contended was an unnecessary extravagance and should cease. Arrangements were made for payment in lieu of these meals, thus dispensing with the ancient position of The Guard as part of the royal household.

When William IV decided that no more civilians were to be allowed in The Guard, he commanded that lists of retired officers and non-commissioned officers, recommended for distinguished service in the field, desirous of becoming members of his guard should be kept by the Commander-in-Chief; and that when vacancies occurred selections should be made from these lists and submitted to the Captain of The Guard for final approval. The Lieutenancy was assigned to a Colonel or Lieutenant Colonel of the Army or Royal Marines; the positions of Ensign and Clerk of the Cheque were to be held by a Lieutenant Colonel or Major; and Exons were to be selected from Captains.

As far as the Exons were concerned, it became the duty of the Captain to lay before the sovereign the names of four officers from which one was to be chosen. It has always been considered the privilege of the Captain to present prominently the name of the officer he wished to see appointed, and this selection has almost always been confirmed, though of course the monarch reserved the royal prerogative of confirmation. Promotion to the higher grades of Clerk of the Cheque and Adjutant, Ensign and Lieutenant now takes place within the corps. The Captain exercises the right of approval of all Warrant Officers and Sergeants selected by the Commander-in Chief for appointment to the rank of Yeoman.

The Yeomen are divided into three Divisions and undertake at least eight duties in the course of a year. Although the function of guarding the outer doors of the royal palaces no longer comes with their jurisdiction, any State duties to be performed inside the palaces are undertaken, as they always have been, by Yeomen of The Guard. Click here for details about Body Guard Duties, The Beefeaters and Further Reading.