In Memory of YBH Robert Arthur Shergold

Robert "Bob" Shergold passed to the final RV on 6 January 2026 aged 92 yrs old.

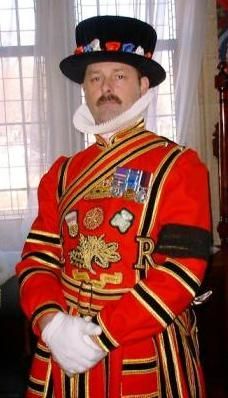

Prior to his appointment to The Yeomen of the Queen's Body Guard of the Yeomen of the Guard on 4 Oct 1988 Bob served in the Royal Air Force as a Master Air Load Master Warrant Officer (Master Aircrew). He joined the RAF on 24 October 1954 aged 21 yrs and served 34 years.

In Bob's 15 yrs career with the Yeomen of the Guard he attained the rank of Yeoman Bed Hanger and moved to the Exempt (from duty) List on his 70th birthday on 11 December 2003.

"We give thanks for all members of the Body Guard living and departed. Give ear, O God, to the prayers of thy people, that our service may take such good effect as thou may be glorified, thy Church, our Sovereign, and country preserved, and every enemy of the truth so utterly vanquished that we may have continual peace, through Jesus Chris our Lord." Amen